H.G.Co. Petticoat Beehives

by H.G. "Bea" Hyve

Reprinted from "Crown Jewels of the Wire", December 1995, page 13

(For background information on this subject, please read the following

articles from Crown Jewels of the Wire: "H. G. CO. Petticoat Beehives ",

2-76-p. 2; Corrections, 5-76-p. 23); "H. G. Co. Petticoat Beehive Update

", 7-79-p. 3; "A Short History of the Hemingray Glass Co.",

1-82-p. 3; (Corrections, 2-82-p. 39.) During the 11 years that I have been

working on this essay, I uncovered, along with other historical data, a letter

(Figure 18) and a photo (Figure 20) relating to Hemingray. Although these items

don't relate directly to the subject matter here, I have included them anyway

because they will be of interest to Hemingray enthusiasts. Neither item has been

published before, to my knowledge.)

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

-

The beehive style is a favorite among many insulator collectors. Some

specialize in all beehives, while others choose just one particular company.

The beauty of their many colors, their sleekness of design, and the profusion of

shapes within the basic beehive style, all contribute toward making them an

extremely popular insulator. In this article I will take just one company and

one style of beehive, the H. G. CO. PETTICOAT, and study its attributes at close

range. I'll explore the meaning of the various embossings, explain why there are

so many colors, and describe the three basic style variations. We'll discover

when, and for how long they were made, along with learning much more about these

gorgeous collectables.

SOME STATISTICS

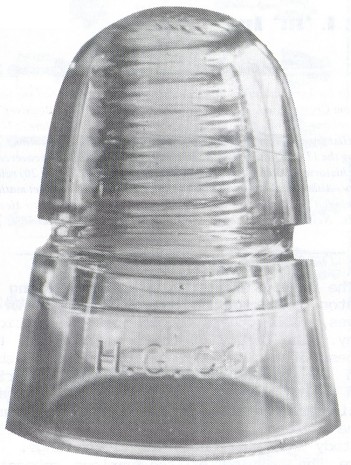

The insulator under discussion here is made of glass and is of a rounded

conical shape. (See Figure 1) Variations aside, it has a 3-1/4" diameter at the

base, is just short of 4-1/4" tall, and weighs 1-1/4 pounds. The embossing is on the

skirt front ("H. G. CO. ") and back ("PETTICOAT"), and there can be skirt

and crown letters. These beehives come in almost every insulator color, and are

usually regarded as communication insulators only.

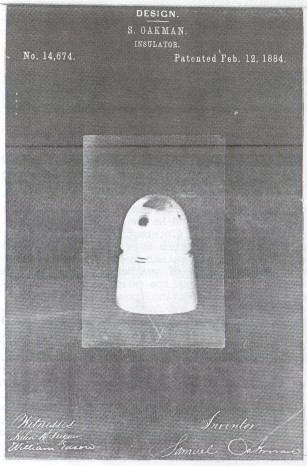

Figure 1

Poetry in glass...

the H. G. CO. PETTICOAT beehive

Shown actual size

(Courtesy

of Chris Hedges)

THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE "BEEHIVE" DESIGN

Very early telegraph insulators were hardly more than glass cups which sat

upside-down on a wooden peg. Although they presented several problems, they

were the beginning of an industry that would last well over a century; down to

our day. Hundreds of improvements were made in insulator designs throughout the

years, in various attempts to find a better insulator.

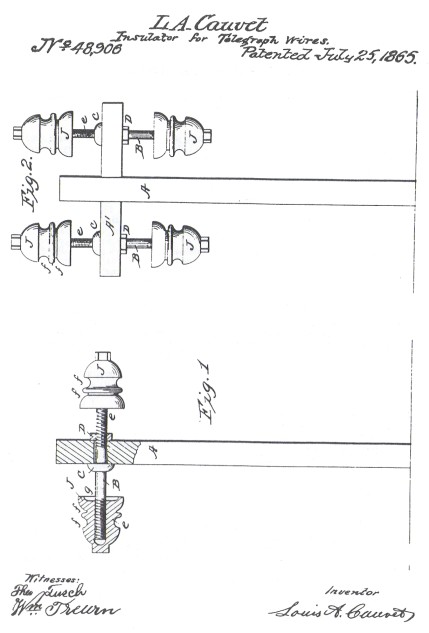

Probably the greatest

beneficial effect on the industry was the invention of a screw-threaded cavity

(threaded pinhole) for insulators by Louis A. Cauvet. He was granted letters

Patent No. 48,906 on July 25, 1865. (See Figures 2 and 3) This innovation

allowed for insulators to be screwed onto a matching screw-threaded pin,

eliminating countless problems. This was the first link in the chain of events

leading to the creation of the H. G. CO. PETTICOAT beehive.

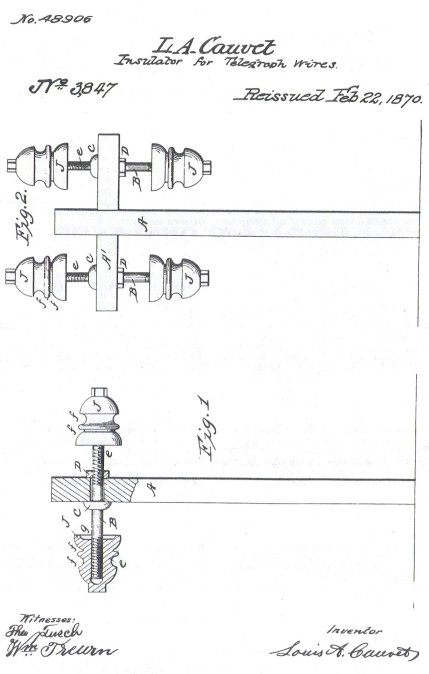

This patent was

reissued on February 22, 1870. (See Figures 4 and 5) A patent reissue is allowed

when it is proved that language in the original did not in some way convey the

proper meaning. There are a number of slight changes, and the exact reason for

the reissue isn't known; but there was a bitter legal battle between Brookfield

and Homer Brooke over the thread patent during those years. The request for the

reissue could have stemmed from that.

Large Image (257 Kb)

Figures 2 and 3

Letters Patent No. 48,906

by Louis A. Cauvet

(Courtesy of

N.R. Woodward and Elton Gish)

Large Image (81 Kb)

Figure 3

Large Image (237 Kb)

Figures 4 and 5

Reissue of Letters Patent No. 48.906

by Louis A. Cauvet

(Courtesy of N.R. Woodward and. Elton Gish)

Large Image (92 Kb)

Figure 5

Large Image (265 Kb)

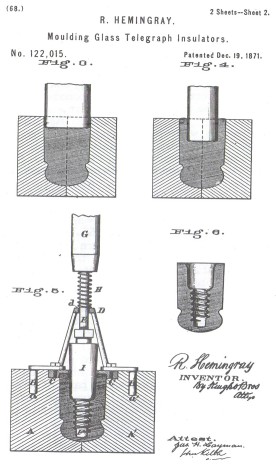

Figures 6, 7, and 8

Letters Patent No. 122,015

by Robert Hemingray

(Courtesy of N.R.

Woodward and Bill and Jill Meier)

Large Image (46 Kb)

Figure 6 (cont'd)

Large Image (145 Kb)

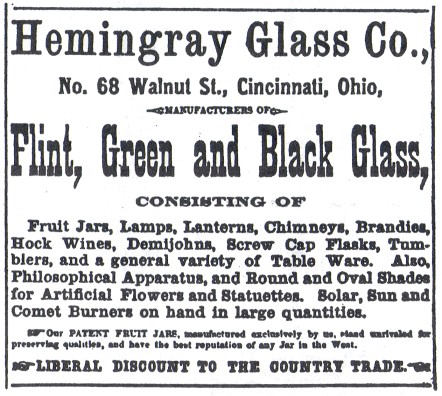

Figure 6-1/2

Company ad from

Williams' Cincinnati Directory and Business Advertiser

1871

(Courtesy of Glenn Drummond)

Large Image (103 Kb)

Figure 7

Large Image (141 Kb)

Figure 8

The second link was formed on December 19,

1871, when Robert Hemingray was issued letters Patent No. 122,01 5 for "a new

and useful process in molding telegraph insulators". (See Figures 6, 7, and 8)

It dealt primarily with the forming of the cavity of the insulator, by first

forming the wider unthreaded portion, then forming the threaded deeper portion.

However, of more significance than the two separate operations in forming the

skirt and pinhole, was the "yielding collar" . It formed the area just

below the thread, and also compensated for variations in the amount of glass in the

mold by increasing or decreasing the length of

the skirt. We have all seen some pieces where there was altogether too much

glass and hardly any skirt at all. This press feature is opposed to the

Brookfield presses of that era that made the thing collectors call

"swirl-start" threads, where the mandrel was screwed into the hot

glass, and there was nothing to form a definitive boundary between the base of

the thread and the skirt.

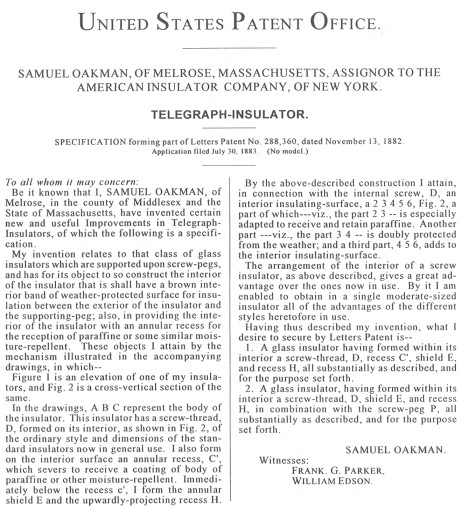

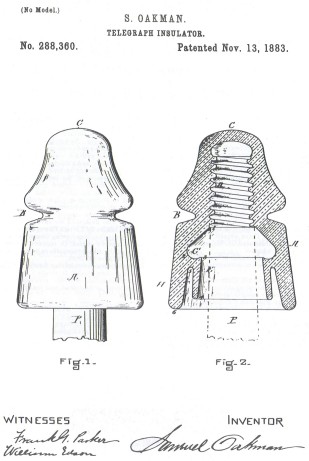

The third link in the chain was forged by Samuel Oakman with his invention of the double petticoat*, for which he received

letters Patent No. 288,360 on November 13, 1883. (See Figures 9 and 10) (The

petticoat design had been around since the October 15, 1872, patent by Oakman,

but that had dealt mainly with construction details of the plunger for making

the segmented threads, and the patent was for a recess to hold paraffin.

Although we have no proof of when these particular insulators were made, it does

seem that they were made prior to 1883, and the prominent mention of the

paraffin recess along with the double petticoat was an attempt at belated

patent coverage of a feature that had been used for some time. The only

connection to earlier patents is that some of the Oakman insulators that bear

the date of the October 15, 1872, patents also have double petticoats.)

- - - - - - - - - - - -

* Insulators are correctly referred to as "double petticoat" even

though the outer surface is actually the skirt. But the term "double

petticoat" has become the "correct" word to use.

Large Image (188 Kb)

Figures 9 and 10

Letters of Patent No. 288,360

by Samuel Oakman

(Courtesy of N.R. Woodward)

Large Image (60 Kb)

Figure 9-1/2.

Newspaper article about new storeroom in the

Covington Daily Commonwealth

February

1, 1881

(Courtesy of Glenn Drummond)

Large Image (117 Kb)

Figure 10

(Note paraffin recess "C")

Let's

expand on this a bit to perhaps clarify it. In order to secure a patent on an

item, it is necessary to represent a part of the construction of the item as

being new and original. Oakman wanted to claim rights to the double petticoat,

but without the paraffin recess, it could be correctly argued that the patent

wasn't valid, because that feature had been used for some time prior. So, in the

first section of his summary, he specifies the paraffin recess, while in the second section he leaves this out, and the text is written so that it

would

apply to any double petticoat insulator. This was an attempt to put the entire

design through as a package deal. Evidently Oakman was successful, since his

patent was used for many years as applying to the double petticoat feature. (The

paraffin recess would not have been practical, was never used to any extent, and

would have been a nightmare for glassmakers.)

So, Samuel Oakman is generally

credited with the invention of the double petticoat or inner skirt, used for the

purpose of creating a greater non-conducting surface on the insulator. And

Hemingray may have believed that he could not be held in violation for making

double petticoat insulators so long as they did not have a paraffin recess, and

he was, of course, correct in thinking that. (Interestingly, Oakman never

referred to this feature as a petticoat or double petticoat. In his patent specs

he calls it "a broad interior band of weather-protected surface for

insulation between the exterior of the insulator and the supporting

peg...". "Petticoat" is certainly easier and faster to write!

However, the word "petticoat" was in use as early as 1888.)

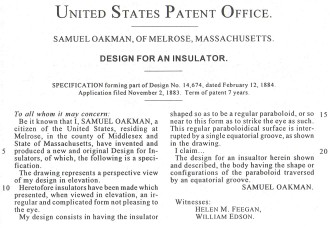

These

three links, the patents by Cauvet, Hemingray, and Oakman, completed the

chain of events necessary for the birth of the beehive. On February 12, 1884,

about three months after the petticoat patent, Oakman was issued Design Patent

No. 14,674 covering the beehive shape. (See Figures 11 and 12)* (A design patent

is a totally different thing from a letters patent. The design patent relates to

an exact and specific appearance of an article, rather than to any practical

application. There are only a very few design patents relating to insulators. )

- - - - - - - - - - - -

* Figure 11 intentionally does not show interior detail, because that was not

to be a part of the patent claim. The illustration has that narrow groove

that belongs to those earliest Brookfield pieces with the 1870 date; later

ones have a larger groove, not shaped to accommodate a wire with essentially no

play.

Large Image (325 Kb)

Figures 11 and 12

Design Patent No. 14,674

by Samuel Oakman

(Courtesy of N. R. Woodward and

Elton Gish)

Large Image (95 Kb)

Figure 12

Large Image (98 Kb)

Figure 12-1/2

Company ad in the Covington City Directory

1878

(Courtesy of Franklin Jaquish

and the Kenton County Public Library)

Again, Oakman did not call his new design a "beehive". This

nickname, as well as a number of others that are used by collectors, was

introduced by John C. Tibbitts in 1967. It was never used by manufacturers or

anyone else prior to its introduction in his first insulator book that year.

Listen to how Oakman describes his insulator in his patent spec.

"Heretofore insulators have been made which presented, when viewed in

elevation, an irregular and complicated form not pleasing to the eye. My design

consists in having the insulator shaped so as to be a regular paraboloid, or so

near to this form as to strike the eye as such. This regular paraboloidical

surface is interrupted by a single equatorial groove." This "paraboloid

traversed by an equatorial groove" is our beehive of today!*

More in Part 2 next month...

|